Was the ‘nuclear’ family an ideal in Early Modern England?

An English Family at Tea, c.1720, Tate Modern, ref: N04500.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/van-aken-an-english-family-at-tea-n04500

When thinking about the nuclear family, what springs to mind? – Well, stereotypically it’s a married couple typically with at least two children. However in early modern England, a household would have consisted on a lot more than this. Richer folk would have had a number of servants, who may have lived in their home, who would be considered as part of the household. Members of the poorer population may have been lucky enough to have some sort of servant or maid who lived with them as well. But, does this mean that each household on the spectrum of class was considered to be a ‘nuclear’ family? Or were they considered as another form of family?

The Idea of Family and Households in Early Modern England

The idea of family and household in the 17th and 18th centuries can be viewed as a relatively complex ideal – it wasn’t set in stone of the family types, and would have varied through the class system. The lower classes would have had a smaller family structure and a very small household. Whereas, the upper classes would have had a larger family structure.

Artist Joseph Van Aken painted two parallel pieces of artwork looking at the view of family in the 17th and 18th centuries. His painting titled ‘An English Family at Tea‘, which was painted around 1720, shows a well off family and also features possible members of their household (below). The painting shows various members of the household engaged in some afternoon tea. There appears to be the members of the family consisting of the widowed wife, the daughter and possible son. It also includes members of the household – maids and other servants. The central figure to the painting seems to be the maid who is serving the tea for the woman dressed in black garments; most likely the matriarch of the family. The fact that she is dressed in black leads us to believe that she is most likely a widow – the woman sitting to her left is most likely her daughter. The men surrounding these women could possibly be prospective husbands coming to visit, or a son and a selection of the male servants of the household.

Joseph Van Aken, c.1699-1749

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N04500

Joseph Van Aken, c.1699-1749

http://www.artuk.org/artworks/saying-grace-141453

His parallel painting titled ‘Saying Grace‘, again painted around 1720, shows a less well off family and their small household (above). One of the more notable differences between the paintings is the use of colour – in ‘An English Family at Tea‘ there seems to be slightly brighter colours used, on the contrast, in ‘Saying Grace‘ there are much darker colours used. The family appears at the centre of the of the painting, and are visibly a much smaller household. This family could possibly be a nuclear family as both maternal and paternal figures are present. Aken’s painting highlights the act of taking communion which was most likely a daily activity for the family. The woman on the left could be an older servant – who, with age, is superior to the other serving ladies. One more likely explanation for the family in the painting is a widower with children who has remarried so his young children have a mother. One key thing to note about this painting is that the man would be considered the head of the household, whilst the woman runs the household. In contrast, in Aken’s parallel painting, it appears that the woman is both head of the household and runs the household.

This difference could possibly be a comment on the structure of a family, on different social levels. In higher social levels, with the lack of a male presence, the woman appears to be the head of the household as well as running the household. In the lower social levels, the head of the household appears to be the man – even with the presence of an older woman, the house is still headed by the male and run by the woman. This would suggest that in the higher social classes, that the head woman of the family held some form of social power. However, if her son was of age when the head male of the family died, then it would be most likely that he would have taken over as head of the family. So it would only be when there is a lack of male heir that the matriarch of the family would have some power.

If we use these sources to think about family in early modern England, we can use them to look at typical family types for both ends of the social class spectrum. However, would we define these families as ‘nuclear’?

Well, I would certainly class the family of ‘Saying Grace‘ as a nuclear family. The man at the very right can be considered as the head of the family, having taken a wife – possibly the woman on the far left – and having young children. The older woman sitting next to the man on the right, could possibly be his mother, meaning that she could be considered as both extended family and immediate family. Due to the close proximity of the family, and the fact that relatives would have heavily relied on each other, I would therefore class this family as a ‘nuclear’ family.

Looking at ‘An English Family at Tea‘ in comparison, I would class this family as a ‘broken nuclear’ family with the addition of a household. The reason the nuclear aspect is ‘broken’ per se, is due to the fact that there is a lack of a clear patriarch of the family. There doesn’t appear to be a clear central family, like ‘Saying Grace‘, and members of the household are present. So, we could say that actually this painting is actually depicting a higher class social household.

Overall, you could say that Joseph Van Aken’s paintings showed two very types of family on the social spectrum in Early Modern England. ‘An English Family at Tea‘ shows the stereotypical upper class household, whereas ‘Saying Grace‘ shows a stereotypical lower class household.

John Opie, 1761-1807

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05834

In comparison, John Opie’s ‘The Peasant’s Family‘ portrays a slightly different family type. At first glance, this appears to be a single mother with two small children; however, at another glance the central woman herself looks quite young, so she might be seen as the eldest sibling. You could say that this is a painting showing three young sisters, and their dog, going out to collect water to help their mother who is at home whilst their father is out working – the ambiguity of the painting, means that there are many possible interpretations of what’s actually going on. The background of the painting is also very generic, meaning that it is hard to identify where these girls are.

Another thing that strikes me as quite interesting is the fact that the younger girls are dressed in the same fashion, although the youngest has no shoes on her feet. In contrast, the older girl is dressed more age appropriately – I would place her between the ages of 16 and 20. If she is indeed the older sister, rather than the mother, then she would have most likely cared for the children whilst their mother tended to the household duties. She may also fulfil this duty until she herself married – and possibly until she has children of her own.

This leads us to question whether this family portrayed in the painting can be considered as a ‘nuclear’ family. Well, I would say at first glance it appears to be a maternal figure with two young children; however, would this be considered as a ‘nuclear’ family or just a type of family present in the early modern period? I guess you could say that this family is a type of ‘nuclear’ family in the early modern period. As Aken’s paintings show, the idea of family varied meaning that it wasn’t necessarily set in stone of what constitutes a family. Therefore, we could argue that due to the different variations of family in the early modern period, we cannot give the ideal surrounding family one set definition.

Overall, you could say that John Opie’s painting shows another family type in Early Modern England. Where Aken shows two types of family on the social spectrum and what constitutes their family and household, Opie focuses on a lower class family who look like they are on the poorer end of the social spectrum. In Opie’s family, there is no form of household and it seems to focus more on the women that make up the family – which could be a comment on how women can be seen to be the central aspect that makes up the family. Not only did women run the household and home, but they were also the emotional head of the family; meaning they arguably had more responsibility in the home, whereas, the men had more responsibility outside of the home.

Beliefs Surrounding Family and Household in Early Modern England

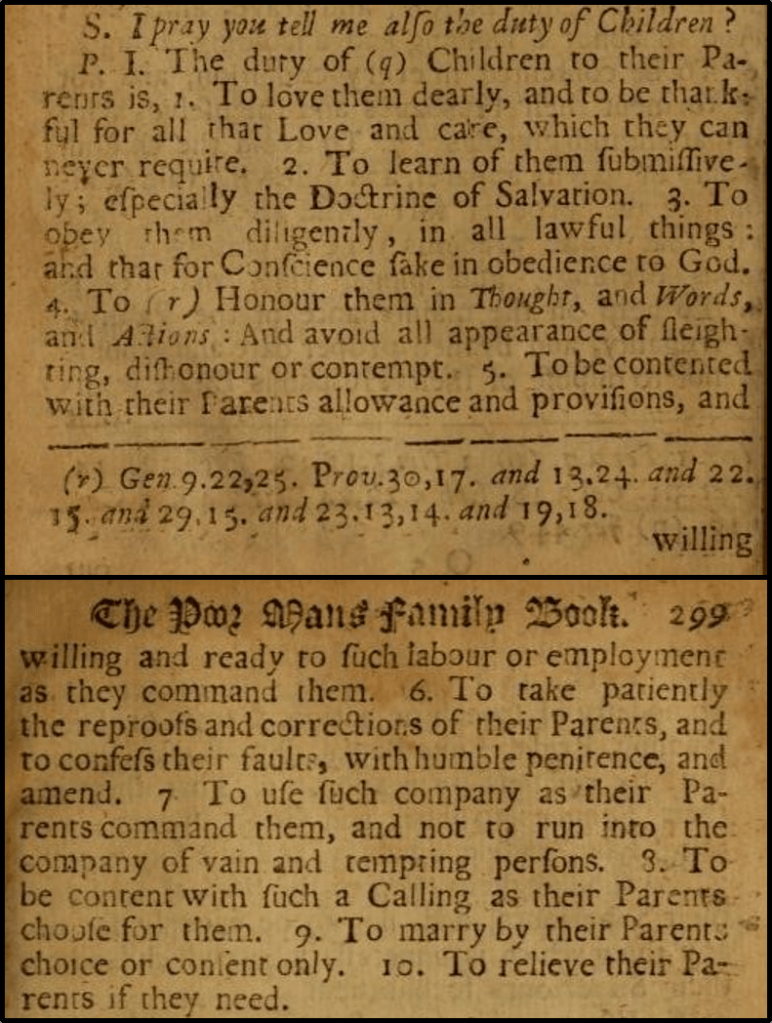

Pages 298-299

The above source outlining a children’s duty to their parents, is an extract from Baxter’s 1684 publication ‘The Poor Man’s Family Book‘. The book would have been given to tentants from their landlords as away of spreading ideals surrounding family and household – as well as circulating Christian ideals. However, the book would have only been beneficial to those members of society who could actually read; many of the poorer classes were most likely illiterate, so wouldn’t have necessarily benefitted from the publication even though it was aimed at them.

In this extract, there are 10 duties outlined aimed at the children; which mirrors the Bible’s 10 Commandments. The main gist of the duties is that the children should always love and care for and obey their parents, and that they should never speak a bad word against their parents or be cruel to them. As well as this, if you look at the bottom of page 298 of the publication, there are references to the bible – notably, Genesis and Proverbs. Both of these examples show the heavy religious ideals that would have been published in books in the early modern period. In this sense, the book is almost saying that if the children disobey these duties, then they are also disobeying God. It also suggests that the Bible almost “backs up” what Baxter outlines in his publication; he’s practically saying this is how you should behave towards your parents because it says so in the Bible. This would suggest to us that the beliefs surrounding children and family in early modern England, were notably focused around religion. The fact that books such as Baxter’s were published, would suggest that the ideal surrounding family and household was almost central in social circles. Even at the lowest level of the socio-economic spectrum, the idea of a structure to the family seemed to be prevalent.

As reflected in the above source, Linda Pollock makes a similar argument about children’s duty to their parents. She argues that many parents “to the best of their ability, made financial investments into their children”, which they hoped would later be reciprocated (Pollock, 2017). This mirrors the tenth duty as outlined in Baxter’s books; that children should ‘relieve their parents if needed’. This would suggest that children were essential to the family structure – meaning that a family could be classified as ‘nuclear’, due to – during their younger, formative years – the children would have been the central focus of the family.

Overall, Baxter’s publication arguably tells us a significant amount of beliefs surrounding family and household in the early modern period. A ‘good Christian household’ would most likely possess this publication and it would be read to the children, so that they knew what their duty was to their family. It also highlights that even at the lowest social levels in society, having a good family structure and functioning household was seen as important.

Was there such thing as a ‘nuclear’ family in Early Modern England?

When thinking about family in the early modern period, it can be hard to categorise families into one type due to the wide socio-economic spectrum. If we try and apply Twentieth-Century ideals to Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century ideals, it will be hard to do so – what we may consider to be one type of family for the poorer population, may differ greatly for the wealthier population. For example, for the poor we might class their families as extended – due to many generations either living under one roof, or older generations relying on the younger ones. Whereas, for the rich we might class their families as nuclear plus a household – due to the married couple living in their house with their children and possibly space for their immediate servants. Therefore, we could say that some form of a ‘nuclear’ family existed in the early modern period. However, we could also say that the family types were just as diverse as they are today.

When thinking about servants as part of the family household, we might suggest that they were indeed part of the family. Taking you back to Aken’s painting ‘An English Family at Tea‘, the servants are included; meaning that, arguably, they are considered as part of the family. In Cavert’s review on Richardson’s book on Servants in Early Modern England, he notes that the argument is made that “a godly, obedient servant […] was said to be an important part of a functioning household” (Cavert, 2012). This would suggest that servant were seen as important in the family and household structure – consequently, meaning that they are considered as members of the family. In addition to this, according to Cavert’s review, Richardson also argues that a servants place within the home of the elites “could make them powerful”, and that many of their masters or mistresses were fearful of their servants’ “ability to defame them through gossip or litigation” (Cavert, 2012). This would suggest that servants were a very important part of the family household in early modern England. The fact that they had the power to ‘defame’ their masters and mistresses, means that they arguably had some sort of social influence in certain social spheres – meaning that they were considered as important members of the family.

If we then look at the ever-changing aspects of family, and what constitutes a family, we might again turn to Linda Pollock. She makes the argument that the concept of family was “constantly changing”, and that a family wasn’t “allotted – that is given at birth – as continuously created” due to the nature of “members” joining and leaving as time went on (Pollock, 2017). This constant state of fluctuation in what constitutes a family means that it is relatively hard to define families as one set state. In support of Pollock, O’Brien also notes in her study that what made a family in the early modern period was ever-changing. In her study of poor families in early modern townships, due to “rising tension about social status” and the “distress caused by deaths of children”, what constituted as a family was continually changing (O’Brien, 2014). From this, we might say that the original structure of the family did start out as what we consider to be a ‘nuclear’ family, but with the changing socio-economic status and aspects of change out of the family’s control, what we define the early modern family as also changes in turn.

So, could we label early modern families as ‘nuclear’? – Well, Pollock mentions the term when looking at poorer family structures. She makes the argument that the “most frequently recorded form of hardship affecting the poor was the breakdown or failure of the nuclear family” (Pollock, 2017). Here, it appears that the poorer families are indeed labelled as ‘nuclear’; leading me to question whether the definition of nuclear families was different in early modern England compared to now. However, the constant changing of the family structure – and ‘breakdown of the nuclear family’, as Pollock argues – leads me to believe that we cannot define families in the early modern period as ‘nuclear’ due to the fluctuating nature of the family structure.

To sum up, artwork and publications of the early modern period can tell us a lot about family, and the ideals surrounding it. However, there is a lot of ambiguity in looking at the family structure of the early modern period. Your social status would also affect your family structure and household structure; meaning that what we define as a family and a household would also depend on the socio-economic status of the people within it. Therefore, I would suggest that the ‘nuclear’ family was not present in the early modern period; however, we could say that a form of the ‘nuclear’ family was present and that due to the fluctuating nature of the family, what we define as a family in the early modern period also changes.

Bibliography:

Baxter, R. (1684) The Poor Man’s Family Book…With a Request to Landlords and Rich Men to Give Their Tenants and Poor Neighbours Either The or Another Fitter Book. London: B. Simons. https://archive.org/details/poor00baxt.

Cavert, William. “Household Servants in Early Modern England”. The Historian 74, 1 (2012): 167-168.

O’Brien, Karen. “Companions of Heart and Hearth: Hardship and the Changing Structure of the Family in Early Modern English Townships”. Journal of Family History: Studies in Family, Kinship, Gender, and Demography 39, 3 (2014): 183-203.

Opie, John. The Peasant’s Family. c.1783-5. Oil paint on canvas. 1537 x 1835mm. Tate Modern, London, England. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/opie-the-peasants-family-n05834.

Pollock, Linda. “Little Commonwealth I: The Household and Family Relationships”. In A Social History of England, 1500-1750, edited by Keith Wrightson, 60-83. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Van Aken, Joseph. An English Family at Tea. 1720. Oil paint on canvas. 994 x 1162mm. Tate Modern, London, England. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/van-aken-an-english-family-at-tea-n04500.

Van Aken, Joseph. Saying Grace. 1720. Oil paint on canvas. 35 x 30cm. The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, England. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/saying-grace-141453#.